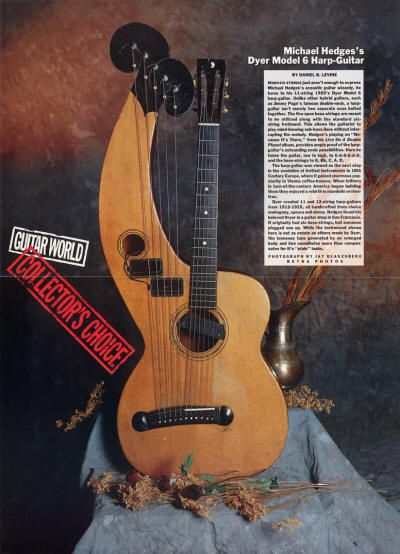

In 1984, Michael Hedges walked into a San Francisco guitar shop and discovered his next musical pursuit: an acoustic relic from the 1920s called a harp guitar.

This discovery would ultimately help revive a bygone instrument for countless musicians, builders, and music lovers the world over.

In the early nineteenth century, harp guitars were popular among classical players, particularly in Vienna. Harp guitars gained enormous popularity in the United States from 1900 through the 1920s. But by 1930, with the arrival of the Jazz Age, cinema, radio, and new music trends, the harp guitar had effectively vanished from the public eye. Thousands of these instruments would sit in attics, basements, and pawn shops across the country; in 1984, one of these harp guitars—a 1922 Dyer harp guitar—would be hanging on the wall of the Satterlee and Chapin guitar store in San Fransisco.

When Michael spotted it, he immediately thought,

“That’s for me!”

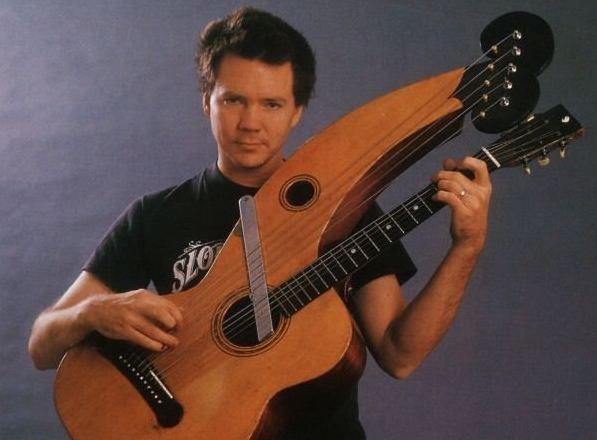

He was drawn to this guitar with five additional bass strings. Hedges had a particular affinity for the sound of open strings and powerful bass frequencies. This eleven-string harp guitar included six guitar strings and five sub-bass (“harp”) strings. He purchased the instrument for $350—less than the cost of the custom case he purchased to take it on the road.

Hedges first played a harp guitar owned by Mickie Zekley in Mendocino around 1983 while attending the Lark in the Morning music camp. He had also heard Pat Metheny play a 15-string Gibson harp guitar on the song “Suite: II. Legend of the Fountain” from Metheny’s 1977 Watercolors album. This piece was inspiring to Hedges. He would later say he had “always wanted one, and I just didn’t have the bucks.” But he was not interested in mimicking Metheny or any other player. He immediately began to explore the instrument with enormous focus.

Hedges brought the necessary discipline and creativity to his new instrument—and with it, he would soon achieve yet another major musical breakthrough.

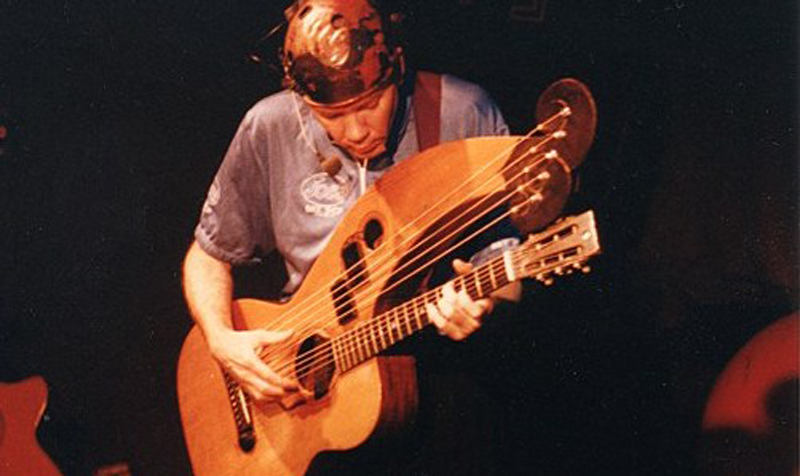

When Hedges began composing on the harp guitar, it would have been natural to play it the same way a guitar is typically played: fretting chords with the left hand and strumming or plucking with the right hand. But on his first harp guitar composition, Hedges never strummed or plucked the six guitar strings—not in the traditional sense—and utilized the five sub-bass strings to maximum effect.

The first piece Hedges composed on his newly-acquired harp guitar was “Because It’s There,” which remains his best-known harp guitar piece. On this piece, Hedges eschewed previous approaches to playing the harp guitar: It was not written as accompaniment, it was a solo piece; Hedges tuned the strings to a unique set of intervals, rather than using a standard tuning on the instrument; and Hedges didn’t utilize traditional left-hand chord-fretting with the right-hand strumming/picking, but instead, he plays much of the melody on the bass strings, while his left-hand uses hammer-ons/pull-offs on the guitar neck to produce rhythmic accompaniment chords. Hedges also uses harmonics played with his right hand—touching his index finger on a harmonic node while plucking the same string with his thumb. Most fundamental to this piece is his use of right-hand string-stopping on the sub-bass strings to preserve the clarity of the bass melody.

► VIDEO: See Michael playing “Because It’s There” in 1986

Hedges explained to an audience in 1988: “This [bass melody] is tricky to do because many of the harp notes must be muted before the next one is played…your thumb has to develop a new consciousness. And there was no instruction manual.” Without flawless execution of this challenging technique, the bass notes would sound muddy, running into each other in a noxious melding of bass tones, not unlike pounding the low-end keys of a piano with an open hand.

The harp guitar brought a new level of musical excitement to Hedges in the same way the guitar had initially inspired him.

By early 1985, he was spending one-third of his practice time on the harp guitar and was planning to record an entire album of harp guitar pieces. This instrument would remain an important part of his musical career from 1985–1997, during which time Hedges would record or perform at least seventeen tunes on the harp guitar.

In 1986, Michael’s earliest harp guitar pieces were featured on the soundtrack of the Japanese film The Story of Naomi Uemura, also known as Lost in the Wilderness. The soundtrack album was released as The Shape of the Land. The film’s subject was the famous Japanese adventurer, Naomi Uemura—who was once called “the greatest solo adventurer since Charles Lindbergh.” Hedges played harp guitar on three tracks from this soundtrack, including his most-iconic harp guitar piece, “Because It’s There.” The soundtrack also contained tracks by pianist Philip Aaberg and guitar pieces by Will Ackerman.

Not long after The Shape of the Land project, a second recording project came along that would again allow Hedges to showcase his newly-crafted harp guitar compositions. Rabbit Ears Production was ready to launch the first of its “holiday classics” series, called Santabear’s First Christmas. They asked Hedges to score the soundtrack. He had already composed a piece for what he envisioned as a planetary-themed harp guitar album, which was never realized. The piece was “The Double Planet,” named after the Earth and moon. It is an engaging tune, and it became the title track of his 1987 live album, Live on the Double Planet. Hedges included a second harp guitar piece on the Santabear project called “Carol Jean,” named after his younger sister. This piece marked his first use of the harp guitar as an accompaniment instrument and the first time he would record a duet with the flute and harp guitar.

► VIDEO: See Michael playing “The Double Planet” in late 1980s

Hedges would continue to expand his repertoire on the harp guitar as he came up with an exquisite arrangement of Bach’s “Prelude To Cello Suite #1” in G major, which was included on the Windham Hill sampler album A Winter Solstice II (1988). Classical guitarists usually play this piece in the key of D. But with the expanded range of the harp guitar Hedges was able to arrange this Bach piece in its original key of G. He arranged this piece in early 1987 and was performing it later that year, but it was not part of his touring repertoire after 1989. He also wrote a vocal tune about world peace on the harp guitar around May 1987 called “Communicate.” He rarely performed this song but recorded a multi-instrumental version of it on his 1994 release, The Road to Return.

The guitar community took notice as Hedges started regularly performing with the harp guitar.

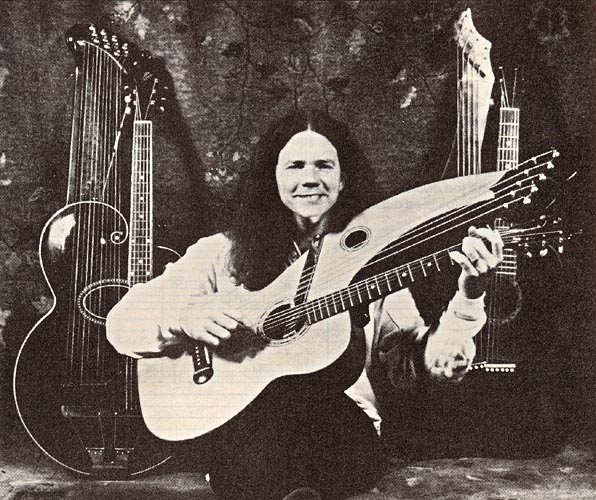

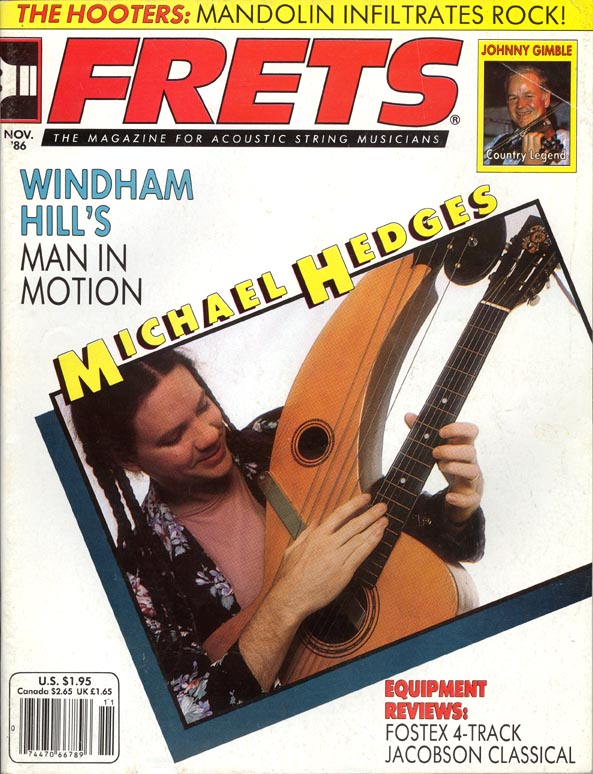

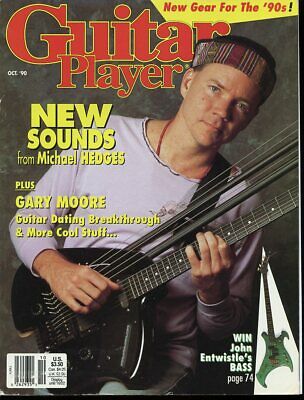

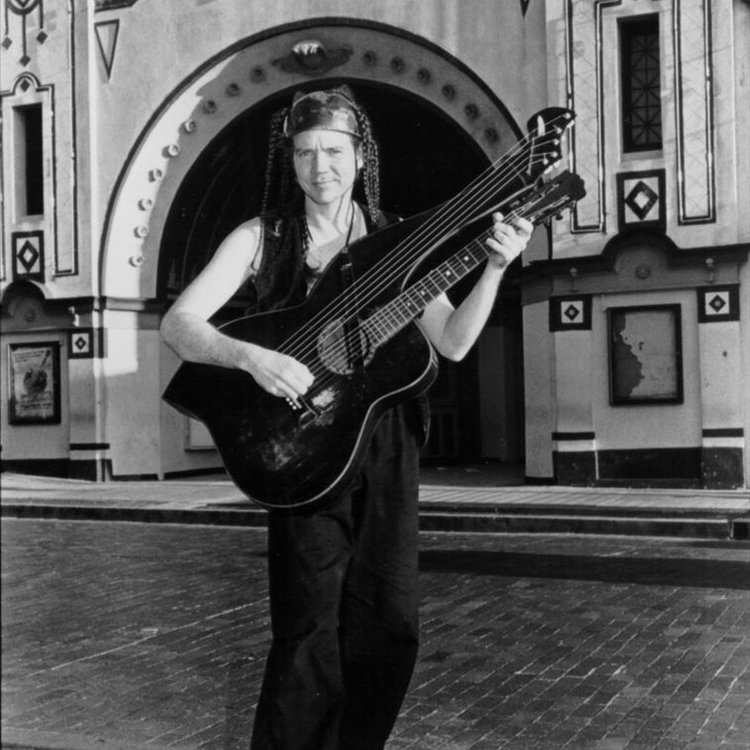

Hedges appeared with his harp guitar on the cover of publications such as Frets (Nov. 1986) and Guitar Player (Oct. 1986, and Oct. 1990), with accompanying cover stories. In May 1988, Guitar World published a one and one-third-page photo spread of Hedges with his Dyer. The Windham Hill in Concert VHS, which featured Hedges, was also getting air time on PBS. With all of this attention, Hedges became associated with the harp guitar, bringing unprecedented attention to the instrument.

Before long, Hedges’ harp guitar inventory would grow from one to four when he acquired three black harp guitars.

The first of these instruments was a black 1913 Knutsen harp guitar. This instrument was often mistakenly identified as a Dyer harp guitar, even by Michael. Although Hedges attempted to purchase a second Dyer, it is unlikely that he ever owned a second one.

The 11-string Knutsen (with six guitar strings and five sub-bass strings) had the same number of strings as his Dyer, but this instrument had a bulkier body and a stylish fin protruding from the lower body. He would name this instrument “Darth Vader” or simply “Darth.” On tour, Darth was sporting a rattlesnake tail wedged under the sub-bass strings at the headstock.

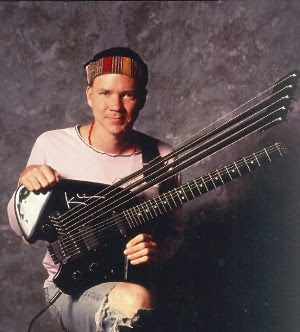

Next up, Hedges purchased a black, Gibson Style-U, 17-string harp guitar. The typical style-U model had ten sub-bass strings, but Hedges’ Gibson was likely a custom order or retro-fit, with eleven sub-bass strings.

After a five-year search, Gibson representative Neil Penner of Enid, Oklahoma, found this instrument for Hedges in 1986. Hedges would give much less attention to the Gibson than his other two harp guitars. The only known use of his Gibson Style-U harp guitar was on his pensive instrumental “Song of the Spirit Farmer,” from the Taproot album.

He recorded the sub-bass strings and played them in reverse as a unique textural accompaniment to the flute melody.

The third black harp guitar Hedges would acquire was in collaboration with guitar builder Steve Klein and culminated in what was likely the world’s first electric harp guitar. As a bonus feature, Klein added the Steinberger TransTrem bridge (with a whammy bar) to this unique instrument. Hedges had used this bridge/whammy bar system on his white Steinberger electric guitar to record his pieces “Point A” and “Point B” (from Taproot).

Adding this feature to this new harp guitar would allow him to perform his Steinberger electric guitar tunes and his harp guitar tunes on one instrument. Plus, this modern harp guitar would mitigate the issues inherent in playing antique instruments: problems with sound, amplification, intonation, and durability on tour. In the winter of 1990, Hedges was performing regularly with his Klein harp guitar, and by 1992 he had named it his “Monster Electric Gorilla Harp Guitar.” He toured with this instrument from 1990–1994.

During the early ’90s, Hedges focused on producing his multi-instrumental album The Road to Return, and the harp guitar was sidelined.

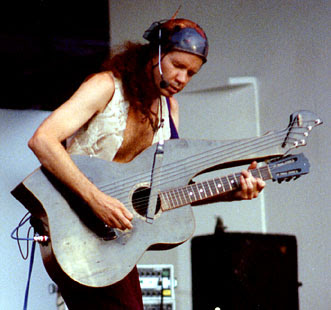

With the exception of “Chava’s Song” and “Song of the Spirit Farmer” on Taproot (1990), he didn’t write/arrange any new harp guitar pieces from 1990–1994. In fact, for most of 1995, he took a break from the harp guitar altogether. But in the fall of 1995, Hedges found a renewed passion for the instrument when he starting performing vocal tunes accompanied by his black harp guitar, “Darth Vader.” On tour, he played his first vocal cover tunes on the harp guitar: “No Expectations” by The Rolling Stones and “Almost Cut My Hair” by his friend David Crosby. He also wrote an original vocal tune on the harp guitar called “Torched.” In his 1996 performances, he added a passionate version of Peter Gabriel’s “Come Talk to Me.”

Since his 1990 Taproot album, Hedges had not recorded with the harp guitar. But when he was asked to contribute to the 1996 Windham Hill compilation The Carols Of Christmas, he arranged a non-traditional version of “What Child is This?” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette called this recording the only version of this traditional holiday tune “with an edge.” Hedges played a brutishly intense, bass-heavy riff on the harp guitar, along with accompaniment on whistles, recorders, and a frame drum. Hedges produced and performed all instruments on this recording. When his Grammy-winning 1996 album Oracle was released, Hedges included this recording as an unlisted track at the end of the album. Streaming services list the track as either “Greensleeves” or “What Child is This?” Hedges’ early website—nomadland.com—explained, “Michael surreptitiously included [this track] on Oracle as well, so hard-core fans wouldn’t feel compelled to buy the [Windham Hill Carols of Christmas] compilation just for his [single track] contribution.” This decision was made without the permission or knowledge of his record company.

In 1997, he once again took up his old Dyer harp guitar. During the last couple of weeks of his final tour in November, Hedges worked out and performed a lighthearted version of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb.” To make this song work on his harp guitar, he needed six sub-bass strings. Typically, his instrument had five sub-bass strings, but fortunately, his Dyer had was built for six. Tour manager Tom Larsen recalled, “For that tune, he had to wire up a sixth string. He had gotten an extra tuning machine from Steinberger that he liked, and he put it on. At the intermission, he would have the monitor tech undo that string so it wouldn’t goof him up in the next set when he had to play ‘Because It’s There.'”

► VIDEO: See Michael playing cover of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb” in 1997

Michael Hedges was the most visible harp guitarist of the 1980s and 1990s, and he is likely still the best-known.

Author and music historian Michael Simmons has written, “Hedges was the first guitarist to really explore the sonic possibilities of the harp guitar….He sparked a small harp guitar revival that has continued to grow.” Hedges’ music played a crucial role in jumpstarting awareness, interest, and demand for this unique instrument. However, he was not the only one to discover this long-lost instrument decades after its decline in the 1930s. Players such as Andy Wahlberg and William Eaton started performing on the harp guitar in the 1970s (and Pat Metheny, mentioned above). But it was in the 1980s that Hedges and others inspired a harp guitar movement. It is rather uncanny that after decades of neglect, around the same time as Hedges, some of today’s notable players independently discovered this instrument, including John Doan, Stephen Bennett, and Gregg Miner. Hedges directly inspired other players to pick up this instrument, including guitar masters Muriel Anderson, Pino Forastiere, Andy McKee, and Don Ross.

Hedges has inspired countless guitarists to play this instrument, but he also inspired many luthiers to design and build new harp guitars.

Guitar historian Michael John Simmons wrote, “[Michael Hedges] was often photographed with a Dyer harp guitar, which he did play quite a bit in concert. These few glimpses of a practically extinct instrument fired the imagination of luthiers and players alike, and over the years there has been such a revival of interest in the harp guitar that there are probably more people playing it today than at any time in the instrument’s history.” Noteworthy examples of Hedges-inspired luthiers include the late Lance McCollum; Michael Greenfield (Greenfield Guitars); Todd Johnston (Oracle Guitars); Anthony and David Powell (Tonedevil Guitars); Scott Holloway and Jim Worland (modern Dyer Guitars); Fred Carlson; Rob Smith (Timberline Guitars); and even renowned Canadian luthier Linda Manzer, who built a 3-neck, 42-string Pikasso guitar for jazz innovator Pat Metheny.

Today, many luthiers are building harp guitars, but there were almost none when Hedges discovered his vintage harp guitar in 1984. Even builders who Hedges has not directly influenced are impacted by the demand for harp guitars that his music helped generate. In recent years, there have been many talented harp guitar-wielding YouTube sensations who are second-or-third-generation descendants from the influence of Michael Hedges—whether they know it or not. Such players continue to spark interest in the harp guitar all over the world.

To conclude, Michael Hedges had three phases with the harp guitar.

In the first phase (1985–1990), he toured with his Dyer and sometimes performed two or even three instrumentals on it per show. He had ambitions to record a dedicated album with the instrument. Instead, Hedges ended up recording most of his early harp guitar pieces across an assortment of recording projects.

In the second phase (1990–1994), he recorded just two harp guitar pieces on his album Taproot (neither was a solo harp guitar piece). He performed with his Klein electric harp guitar on tour and usually only performed one tune on it per show (i.e., “Because It’s There”). After a decade of touring with the harp guitar, Hedges took a break in 1995 for most of the year, saying, “It’s home resting, and mutating [grinning].”

But in this third period (September 1995 through November 1997), he started performing with “Darth” (his black Knutsen) and had a creative revival on the harp guitar. He started writing, arranging, and performing vocal tunes with his vintage Knutsen and Dyer instruments, including a handful of innovative cover tunes. During this period, he performed as many as three songs per show on the harp guitar.

Throughout these three phases, he recorded or performed at least seventeen distinct pieces on the harp guitar. His unique approach to the instrument became a catalyst in the reemergence of the harp guitar, starting in the 1980s, and his influence on players and builders continues today.