By Jake White

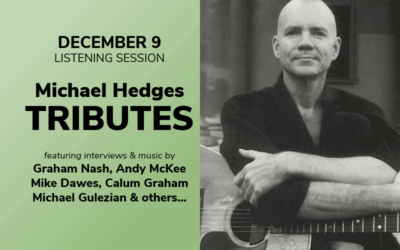

Over the past couple of years, I’ve studied the life of Michael Hedges for my upcoming biography, Dream Out Loud. Tracing his early musical influences has been a fascinating aspect of my research. Each of these influences played a pivotal role in shaping Hedges as one of the most dynamic and innovative composer-guitarists of our time. It has been an honor to interview some of these musicians for this project.

From an early age, Hedges was enamored with all things musical.

Both his parents were musically inclined. His mother, Ruth, played cornet and started her career as a junior high music teacher. His father, Thayne, played piccolo and worked as a university educator and clinician in speech pathology.

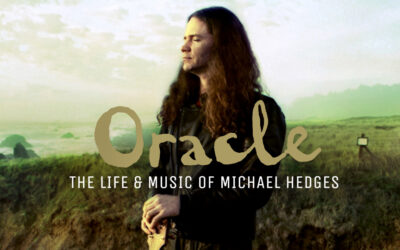

Ruth and Thayne, who first met as students playing in the university band at Phillips University, supported and encouraged their son’s pursuits. One of Michael’s earliest musical experiences was his father taking him to see the John Wayne film “HATARI!” in 1962. Henry Mancini’s soundtrack awakened something profound in young Michael. Even as an eight-year-old, his mind would obsess over the haunting melody of “Theme from HATARI!” a piece he would later arrange and record for solo guitar on his 1996 Grammy Award-winning album Oracle.

Michael took up the guitar in sixth grade after years of piano, cello, and clarinet lessons.

He had at least two guitar teachers during these early years and didn’t particularly idolize either of them. Throughout his career, he cited several early influences that got him excited about pursuing the guitar in his youth: “It was Peter, Paul, and Mary that got me into fingerpicking, and then Elvis got me into the sensuality of it all. And when the Beatles hit, it was just all over for me.” He especially loved the beginning guitar chord of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” by the Beatles, and he was likewise inspired by Elvis’ “Follow That Dream.”

His earliest guitar heroes were John Lennon, Jimi Hendrix, and Pete Townshend.

While in junior high and high school, he formed bands influenced by the music of Grand Funk Railroad, Iron Butterfly, Jethro Tull, King Crimson, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, and The Who. Michael was so enthralled with Pete Townshend that he would mimic him by wearing a white jumpsuit to band performances. Years later, he said, “I think of myself more as the Jimmy Page or Pete Townshend school than anything.”

But Michael wasn’t solely focused on the guitar. Ian Anderson’s flute work in the progressive rock band Jethro Tull motivated him to take up the flute and piccolo and play in the high school marching band, which was a prerequisite for him to participate in the more-desirable concert band as a guitarist and bass player. These opportunities deepened his understanding and enthusiasm for guitar performance.

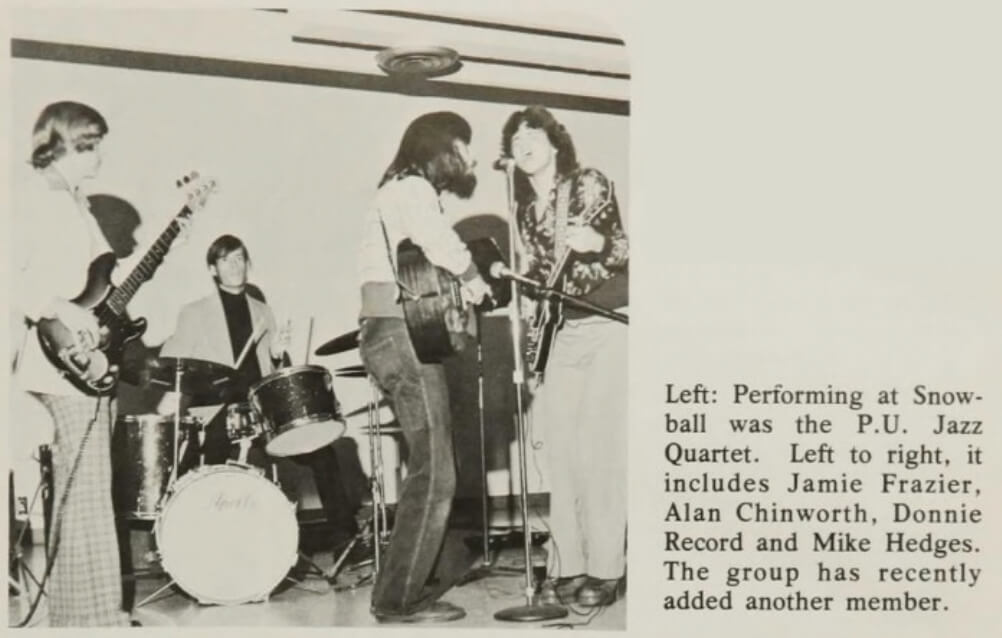

In his early teens, Michael followed a local band called Poverty’s Children (circa 1967–1968), led by local musician/songwriter Don Record. Michael never missed a show. Several years later, Michael developed a close friendship with Don, and they played in a rock band called Rocky & Friends. Their lifelong friendship brought them together for gigs at every stage of Michael’s career, from Baltimore to Palo Alto and Mendocino, to reunions in Enid.

Michael grew up in marching band country. The annual Tri-State Music Festival in Enid, Oklahoma brought marching bands from all over the country to the small university town.

Michael had no problem being the only boy in the flute section of the marching band, though his jock friends were not shy in providing commentary about his band uniform. Hedges reflected in 1988, “I’ve really been getting into marches. I thought about doing an album of marches. The ‘March of the Siamese Children’ from The King and I. Or the ‘March of the Toy Soldiers’ [from The Nutcracker]. I guess it all goes back to my experience in marching band in Oklahoma.”

His song “Follow Through” (1985) and his ensemble piece “The First Cutting” (written circa 1986) are both marches. “The First Cutting” from Taproot was initially called “March” or “Mischa’s March.” Michael explained: “[This next piece] is a march. [It] started out on this little guitar that I bought for my son, Mischa. So I’m going to call it ‘Mischa’s March.’ Or if I lose my temper with him, I’ll call it, ‘Mischa, March!'”

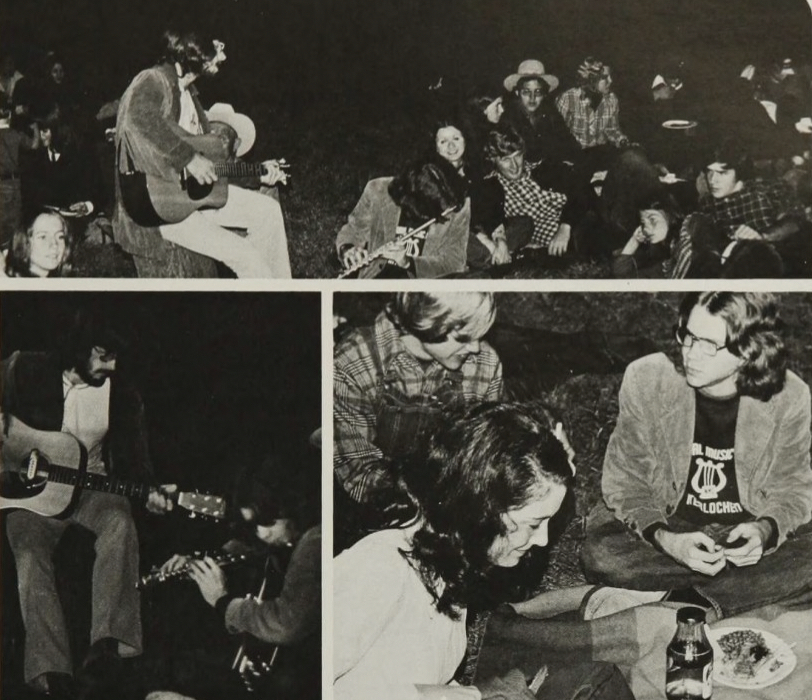

During the 1970–1971 school year, Michael’s father took a sabbatical from Phillips University to teach at Humboldt State College in Arcata, California.

As a result, the Hedges family moved from Enid, Oklahoma, to Northern California for a year—a pivotal experience for Michael. His music and cultural interests were heightened by his exposure to the emerging California singer-songwriter/folk-rock scene. It was eye-opening for Michael to spend his junior year of high school in the thick of the counterculture movement. Michael’s brother Brendan called it a “magical year” for the Hedges family.

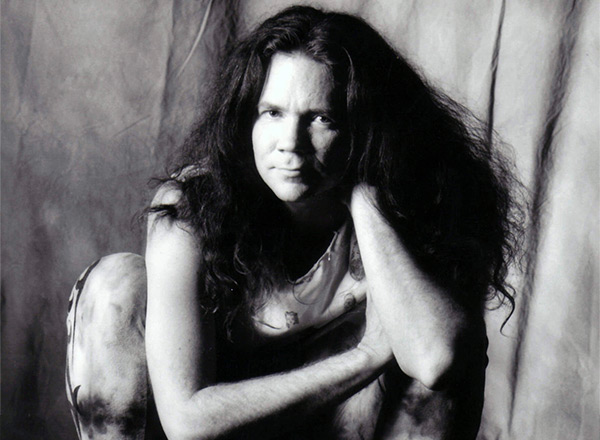

Michael grew out his hair, dated his first girlfriend, and discovered some of his most important and enduring musical heroes, including Crosby, Stills & Nash; Neil Young; and Joni Mitchell. He was particularly drawn to Joni’s use of altered guitar tunings, harmonics, fretting chords over the guitar neck, and rich open-string chords. During this era, Hedges discovered several of his all-time favorite albums: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s Déjà Vu, Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush, and Joni Mitchell’s Ladies of the Canyon. These albums all have superb acoustic steel-string guitar performances using altered tunings. He covered tunes from these albums throughout his career.

Returning to Enid from Arcata and Northern California was difficult for Michael.

California had left a lifelong imprint on him and the rest of his family. (They would all relocate to California in the coming years.) “After that full year, we didn’t realize how much we had changed,” Brendan Hedges said. “When we showed up that first Sunday at church, everybody looked at us. They stared at us. It’s like, ‘What happened to the Hedges?'”

The local newspaper editor asked to take a photo of Michael’s long hair after the service, with the intention of publishing it as an example of what was not acceptable in their community. Michael’s mother told them to “go to hell.” His first day back at Enid High School was no better. They sent him home on account of his long hair. “Very reluctantly, on his own, he went and got his haircut,” Brendan recalls

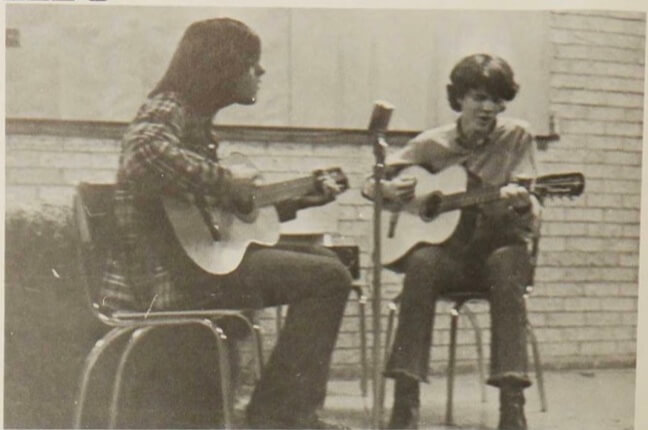

During his senior year at Enid High School (1971–1972) as well as the next three years at Phillips University (1972–1975), Michael attended various music camps, both as a student and a counselor. He studied music composition and majored in flute. He also met and worked with his mentor and friend, Dr. Eugene Ulrich, who guided him in the classroom at Phillips and in private music lessons. From his senior year through his years at Phillips, Michael absorbed Ulrich’s deep knowledge of music, learning everything from sight-reading to 16th and 18th-century composition.

During this same period, Hedges would discover several other important sources of inspiration.

First among these was progressive country singer Willis Alan Ramsey, whose songwriting and guitar playing led Michael to approach the guitar in a new way. Hedges said, “[Ramsey’s] hammer-ons and pull-offs are so rhythmically correct and integral to his style, it made me realize I had a whole other way to pluck the instrument.” At age 18, Michael first listened to Ramsey’s 1972 self-titled album on a record player in the basement of his home in Enid. While lying in the dark with his musician-girlfriend, Shannon, the two of them cried together as they listened to songs like “Spider John” and “Watermelon Man”—both were tunes that Hedges would cover for years.

A second discovery was multi-instrumentalist/songwriter Todd Rundgren, whose music further augmented Hedges’ perspective of harmony, polychords, and songwriting. Michael cited Rundgren’s influence on his early songs, like his unreleased “Last Sad Song” (circa 1980) and chord choices in his instrumental “Rickover’s Dream,” written in 1982. Hedges also attributed Rundgren’s influence as the catalyst for his fascination with electronic music while at Peabody Conservatory and beyond.

Another significant influence from this period was his discovery of Leo Kottke—someone he would later call the “big brother that I never had.” While on a college band trip to New York City (circa 1972-1974), Hedges discovered Kottke’s album 6-and 12-String Guitar (also known as the Armadillo album). Kottke’s tune “The Last of the Arkansas Greyhounds” inspired Michael to experiment with new techniques, such as striking an open chord of harmonics and then hammering on multiple strings to produce unique timbres and chord voicings. From this spark of inspiration came Michael’s first groundbreaking solo guitar piece: “Silent Anticipations.”

As he shaped this pioneering guitar instrumental, Hedges developed a handful of original techniques.

These techniques included hammering on—tapping—multiple strings over the top of the neck with the left hand, several percussive attacks on the body of the guitar using either hand and even raking his pick across the guitar bridge pins (much like the clicking sound of a guiro, a wooden percussive instrument). “Silent Anticipations” always had an improvisational aspect, as he never played it precisely the same way. He performed this tune in nearly every show throughout his career. This piece was the beginning of the unique style of Michael Hedges.

During the early ’70s, Michael wrote solo guitar pieces like the Kottke-inspired “Adrianne” and “Outside Cabin 11,” the latter is an example of his early use of two-hand tapping on the fretboard. These pieces are early indicators that something new and innovative was afoot. But when a teacher turned him on to Hungarian composer Bela Bartok’s “Piano Concerto No. 2,” his imagination took him in another groundbreaking compositional direction on the acoustic guitar.

The expansive chords in the second section of Bartok’s concerto led Hedges to merge his developing composition skills with his newly-found guitar techniques to create a truly original voice on his instrument.

The result was “Breakfast in the Field,” which utilizes the same types of chords (stacked fifths) that Bartok used in his “Piano Concerto No. 2.” The landscape of Oklahoma likewise inspired Hedges’ new piece. He wrote this composition over breakfast while watching the sunrise from a wheat field with his college girlfriend. He wrote “Breakfast in the Field” in an unusual guitar tuning and utilized many innovative guitar techniques.

It ultimately became the title track of Hedges’ first album in 1981.

Looking back on this period, Hedges later reflected: “I was hopelessly in love with all types of music.”

He called himself a “hunter-gatherer,” saying, “I’ll find and use anything I can hunt down.” By the mid-late ’70s, he was listening to ECM musicians, such as Pat Metheny and Ralph Towner. He also studied the work of British folk guitarists such as Martin Carthy, John Martyn, Gordon Giltrap, and Richard Thompson, along with Canadian singer-songwriter/guitarist Bruce Cockburn (check out “Islands In A Black Sky” from his 1973 album Night Visions).

His musical interests continued to expand and diversify after he moved to Baltimore in 1975 to attend five more years of college at the Peabody Conservatory of Music (a blog post for another day), plus an additional year of advanced post-graduate electronic music seminars. He also attended a multi-week computer music seminar during the summer of 1980 at Stanford University under John Chowning, a pioneer in computer music.

As his career took off in the 1980s, Hedges had the honor of meeting many of these early influences on his music—from Peter Yarrow, Pete Townshend, and Pat Metheny to Todd Rundgren, Richard Thompson, and Neil Young—even becoming close friends with his guitar heroes: David Crosby, Leo Kottke, Willis Alan Ramsey, among others. Many of these musicians became fans of Michael’s music. The impact of these early influences rippled throughout Michael’s life at all stages of his musical journey