Written in 1996 for the release of Oracle – from the original Nomadland.com website.

Words by Matt Guthrie DeLange

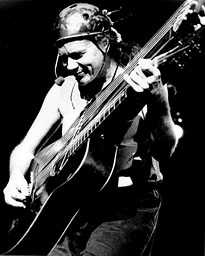

At one of Michael Hedges’ 1993 concerts, a fan jokingly shouted, “Play something unpredictable!”, precipitating a puzzled silence from the crowd and stage.

After a reflective moment, Michael responded matter-of-factly, “I’ve been trying to do that my whole life”, precipitating thunderous applause rivaling any given to his music that evening and speaking volumes about his relationship to his audience.

Michael Hedges is perhaps the most innovative and kinetic acoustic guitarist in the history of the instrument, but he is first and foremost a composer who plays guitar, not a guitarist who plays compositions. His innovative techniques are a means to an end resulting from the demands of his compositions rather than conspicuous attempts at virtuosity. Michael’s embodiment of contemporary composer, innovative guitarist, and flamboyant performer all in one has led to an eclectic style which consistently defies categorization. He has used various tongue-in-cheek phrases to describe his music over the years—“violent acoustic”, “heavy mental”, “acoustic thrash”, “wacka-wacka”, “new edge”, “edgy pastoral”, “savage myth”, “deep-tissue gladiator guitar”—but regardless of what he or anyone else calls it, the fact remains that he has defied classification for over fifteen years while still producing profoundly expressive music on his own terms.

Michael’s life in music began in his hometown of Enid, Oklahoma, where he flirted with various instruments before focusing on flute and guitar.

He eventually enrolled at Phillips University in Enid to study classical guitar, but more importantly, to study under the tutelage of his compositional mentor, E. J. Ulrich. Michael then went on to earn a degree in composition from the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore while concurrently nurturing an interest in electronic music. “I went to the school of modern 20th century composition. I listened to Leo Kottke, Martin Carthy, and John Martyn, but my head was headed more towards Stravinsky, Varese, Webern, and a lot of experimental composers like Morton Feldman.” Michael’s interest in electronic music led him in 1980 to Stanford University’s renowned electronic music department. While playing in nearby Palo Alto, Michael was heard by Windham Hill co-founder and guitarist Will Ackerman, who later recalled, “Michael tore my head off. It was like watching the guitar being reinvented.”

“Michael tore my head off.

It was like watching the guitar being reinvented.”

– Will Ackerman

Just prior to meeting Will Ackerman, Michael met his musical compadre, bassist Michael Manring. The two began their recording careers together on Hedges’ first Windham Hill release, 1981’s Breakfast in the Field, an album which immediately established him as the label’s rebel and the pioneer of an entirely new acoustic guitar genre as profound as that created by his self-described “big brother” Leo Kottke before him. While the album lacked Michael’s unmistakable “Earth tone” which would emerge on later albums, the incredible compositions and performances led fellow musicians from David Crosby to Larry Coryell to note that a new kind of synthesis had been caught on tape.

During the next two years, Michael’s compositional and performance skills exploded in sophistication, resulting in his dynamic “man-band” performances. Combining these developments with revolutionary acoustic guitar amplification techniques, he created a milestone recording unlike anything anyone had ever heard—1984’s Grammy-nominated Aerial Boundaries. The tone, mind-boggling technique, compositional sophistication, and dynamic range of expression on this recording were truly revolutionary. In a sense, Michael had left his previous album in the dust, or as Joe Gore said in his 1990 cover story in Guitar Player, “…the tones and techniques unveiled on his first album had fully matured, and Hedges blew the genre apart.”

By 1985, it had become clear that Michael would not be confined to the limits of instrumental music, or any other category, including “new age”—the genre Windham Hill had essentially created. Consequently, the label created a new subsidiary label, partly to accommodate Michael’s self-described “eclectic record with strange-tuned folk songs”—Watching My Life Go By. “The real crux of the issue is what a composer thinks about when he or she is writing a tune. The term ‘new-age’ doesn’t come into my mind when I’m at my writing table or at my guitar. No categories come to my mind, and I think this is very healthy. If I did have a formula, it would be one more limitation that I would have to deal with, and I’m not in this business to make limitations for myself. I’m in it to get high. That’s what happens to me when I write music.”

1987’s Live on the Double Planet, recorded at concerts across the U.S. and Canada, is a summation of Michael’s development to that point and captures the intensity of his live performance. This album features new and rearranged originals, including two compositions for harp-guitar—a rare instrument few have mastered and fewer still with anything approaching Michael’s grace and range of expression—and three covers, including his ferocious version of “All Along the Watchtower”.

“When I’m writing a piece, I write it entirely for me. When I play it, I play it entirely for the audience and the audience gives it back to me tenfold. I think you always have to keep that live connection going because that’s what music is all about—it’s communication between human beings. Performing is more of a sensual experience—composing is more of a spiritual one. Music goes from human soul to human soul. My approach to music and my approach to life are the same thing. I’m not quite sure what that is, but I’m always thinking about the way I’m living while I’m playing guitar, and I’m always thinking about the way I’m playing the guitar when I’m living. Why think about guitar while you’re playing guitar? Why not think about life? You don’t want to tell people how you’re playing the guitar. You want to tell people how you live. That’s the purpose of playing guitar, from my perspective.”

1990’s Grammy-nominated Taproot, an “autobiographical myth told in music” features instrumental pieces and one vocal composition set to the lyrics of e. e. cummings and was Michael’s first recording in his Northern California studio, The Speech & Hearing Clinic. The concept for Taproot was influenced by the writings of Joseph Campbell and Robert Bly, both of whom encourage the development of personal myths and non-literal imagery to define and deepen identity. “I have troubles like everybody else does. I needed something to put me in balance, so I wrote a story that had symbols of my life in it—as Joseph Campbell would say, ‘a myth to live by’. I finished the story and solved all the problems. Then I took the names of the characters, who represent real people in my life, and the events, which are fictional but symbolic, and made them into song titles.” Michael’s musical catharsis was his most textural and epic to date, ranging from subdued and contemplative ensemble pieces to the “savage myth guitar” of the signature pieces “Ritual Dance” and “The Rootwitch”.

Michael has appeared on the cover of every major guitar magazine, winning Guitar Player’s readers’ poll award for “best acoustic guitarist” five years running—and was subsequently named by the magazine as one of the “25 Guitarists Who Shook the World”—but as Taproot signaled, he had been moving beyond the limits of solo acoustic guitar. “[Guitar Player] retired me to the ‘Gallery of the Greats’. I took that to mean that I no longer have to prove to anybody that I am a guitarist, thus I am now free to pursue other sounds and interests. I don’t want to be limited by what people call a ‘style’. I want to write music as I feel it, not what people expect of me because of what I’ve done in the past.” The result was Michael’s first release in four years—1994’s The Road to Return—a predominantly vocal album with significantly more elaborate arrangements and textures than previous works. In addition to acoustic guitar, Michael performed on flutes, drums, synthesizer, harmonica and electric guitar. “The Road To Return is an internal voyage. Not like a nostalgia trip. More like a vision quest.”

Following The Road to Return, Michael set out on three tours accompanied by Michael Manring. As is typical for a Hedges tour, the performances were not what anyone expected. Michael surprisingly opted to largely ignore material from The Road to Return in favor of introducing many new compositions, a higher percentage of pieces performed on keyboards than ever before, and a foray into yogic performance art. Michael then toured alone for the first time in almost two years, and again surprised many listeners by leaving the keyboards at home and returning his focus to acoustic guitar and harp-guitar. Still more new compositions were featured, including four acoustic guitar instrumentals and his first vocal tune with harp-guitar.

As the abundance of new music indicated, Michael had entered a newly energized and prolific period, which continues to the present. Vocal pieces such as “Torched”, “Rough Wind in Oklahoma”, and “Free Swingin’ Soul”, and the instrumentals “Dirge”, “Jitterboogie”, and “Ignition” all indicated a new diversity, directness, and intensity. To accommodate the plethora of new material, Michael began work on two projects—the first, his latest release, Oracle, and second, the tentatively titled Torched.

Oracle signals Michael’s full-throttle reemergence into the world of instrumental guitar music. With the exception of his vocal cover of The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows”, Oracle is Michael’s most diverse and dynamic instrumental effort to date. The album ranges from the intricate and passionate solo fingerstyle pieces “The 2nd Law” and “Baal T’shuvah” to the driving acoustic thrash of “Ignition” to the smooth groove of “Jitterboogie” to the heart-wrenching “Dirge” and beyond. In addition, the beautiful multi-instrumental title track (originally titled “Fusion of the Five Elements” and eventually renamed for the Arizona town where it was written) represents the maturing of the more elaborate production techniques he had experimented with on The Road to Return.

Like his incredible live performances, Oracle further highlights Michael’s love of pop and rock’s legacies. His arrangements of The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows” (performed as a duet with Michael Manring) and his solo guitar interpretation of Frank Zappa’s “Sofa #1” (which Michael created at the invitation of Dweezil Zappa as part of a guitar tribute to his late father) showcase Michael’s ability to distill difficult compositions to his own instrument. (Michael had the unique opportunity to perform “Sofa #1” for Zappa shortly before his death.) Also appearing on Oracle is Henry Mancini’s “Theme from HATARI!”, a formative piece of music for Michael during his youth, as well as the lovely ballad “When I Was Four”, which was developed from one of his son’s guitar tunings.

If Michael’s art is driven by openness, the fates were on his side just after he finished The Road To Return. At a concert in Oregon in 1994, Michael was approached by a woman who returned a guitar to him which had been stolen from his van fifteen years earlier while opening for Jerry Garcia. The custom guitar (built by luthier Ken DuBourg and heard on much of Breakfast in the Field) was in dreadful condition, but Michael invested in its restoration and the instrument’s presence wound up becoming the inspiration for several of the tunes heard on Oracle.

As Michael points out, Oracle fits perfectly into the chronology of his own life—“The Road to Return was a search for ‘Who am I?’ Then my old guitar was returned and I thought, ‘Yeah, this is part of who I am.’ Now, I’m open. I have a feeling something new is on the horizon for me, because, after all, how many ways can you slap a guitar? Since I’ve been writing songs, I’m more conscious of the music I’m after. It shouldn’t be seen as a new phase of my playing, but just more of me.”

Before his death, Michael was refining new material for the tentatively titled Torched. A preview of some of the predominantly vocal material indicated a synthesis between the elaborate production of The Road to Return and the focused energy of Oracle. One got the sense that Michael had come full-circle, albeit with a wider sweep, and, as much of his new songs suggested, was feeling reborn.

Michael’s genius has always been his ability to use his music as a tool for self-discovery as well as the means for expressing it.

This has never been truer than right now.

Upcoming Michael Hedges Biography

A comprehensive biography of the life and music of Michael Hedges is in development.

“Remembering Michael Hedges” 20-Year Tribute Concert

Read a recap and watch clips from the 2017 Michael Hedges Tribute concert organized by Jeff Titus.

The Early Days of the New Varsity Theater

Michael’s longtime friend and manager of the New Varsity Theater, tells the story of first meeting Michael at the New Varsity Theater.